Marcos Cruz, Marjan Colletti (marcosandmarjan) 2006

Published in: Dialogue: Cross-cultural Exchanges in Architecture, A+T Architecture + Time.

Published in: Dialogue: Cross-cultural Exchanges in Architecture, A+T Architecture + Time.

Shanghai: Tongji University Press, September 2006, pp. 48-53.

Preface: Marjan Colletti and Marcos Cruz – aka marcosandmarjan – are one of those idiosyncratic creative combinations, composed from a curious cultural mix of things variously Portuguese, German, Italian, Austrian and English and a hundred other countries and cities . . . all thrown together in a large pot, given a healthy splash of intellectual thought, a dose of hybrid vigour and tough rigour, and, above all, a tremendous sense of real design flair. The results of this heady concoction are suitably broad - from interests in surfaces and interfaces to shapes and forms to systems and hierarchies to geometry and theory, and all of which are evident (implicitly or explicitly) in the Xiyuan Entertainment Complex described here. What I like most about their work is that while I always think I will be able to recognise something that is truly marcosandmarjan, I am never, ever100% sure - there is always a surprise, an unpredictable shift, a playful move that only they could have enacted. This makes them great designers, great speculators, and great fun. And, of course, great colleagues. They have been running diploma Unit 20 at the Bartlett School of Architecture at UCL since 2003 (and other units since 2000), and they are one of our strongest teams - we love having them teach with us, and we love seeing their – prolific and inspiring – architectures even more.

Prof. Iain Borden

Head, Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

Xiyuan

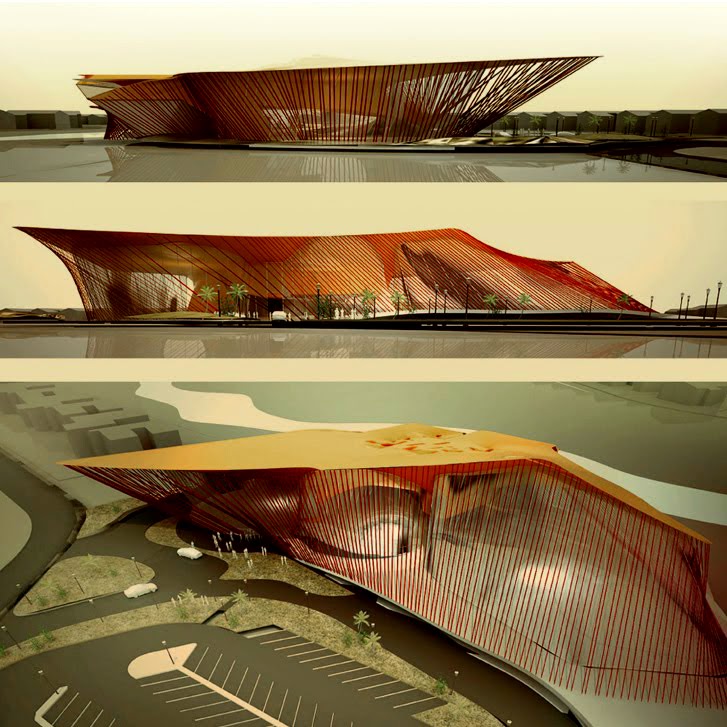

It was high summer. The air was hot and humid, and the sizzling of the dragonflies revealed the close proximity to the adjacent Yiheyuan lake. We were looking eastwards, imagining the sun rising and shining tangentially over what we envisioned to be the vast stone surface of the Xiyuan Entertainment Complex. The atmosphere that day was going to be just magic…

The ‘Big Roof’ masquerade

Back in spring 2004 we had started working on an invited competition for the Xiyuan Complex, which we were later asked to develop further. The brief in that first stage was for a 180.000m2 building proposal on a long strip of land of around 100x750 metres located right in front of the gates to the Yiheyuan Royal Summer Palace in the Haidian district in northwest Beijing. Due to an imposed restriction of the building’s height to 3.3m, and consequently a lack of visibility, we were asked to cover the whole building with a series of traditional Chinese upturned tiled roofs that would give this intervention a conspicuous Chinese face. Here, the ‘Big Roof’ was a mask, a powerful symbol that would link a modern programme to the historical past of the Summer Palace. In the words of the Liang Sicheng the architecture would be ‘wearing a Western suit and a Chinese skullcap’.1 This ‘adaptive approach’ of a Western-style building hidden behind a Chinese-style roof was reminiscent of a long-lasting debate, in which a conceptual binary distinction between the notion of essence, body, foundation, content or structure (ti), as opposed to form, application, use and function (yong) had largely troubled Chinese architectural history.2

In the Xiyuan project, a sequence of distinctive interpenetrating roof structures, along with a series of courtyards—designed as protected yet public spaces—tried to extend the tremendously rich lineage of notable Chinese historical buildings, whilst translating such concepts through the requirements and intentions of a contemporary commercial intervention.

From mono-programmatic to multi-programmatic

Due to uncertainties regarding the financial viability of such programme—so common in contemporary China—the project went through considerable changes in a very short period of time. From an open and very permeable multi-purpose intervention with retail areas, conference facilities and public entertainment in the first stage, the project transfigured in the second stage into a mono-programmatic, large-scale shopping mall, and later into an entertainment complex. Fortunately, the idea of a highly marketed intervention under the brand name of a Western architect, characterised by the fake image of a ‘Big Roof’, was abolished. The roof controversy, however, remained, yet it was turned into a large accessible green area allowing a variety of recreational and sports facilities, which afterwards turned into a large stone surface.

Subtle contextualisation

Meanwhile, morphological and topographical nuances were increasingly shaping the proposal. This was furthered by our conviction that, besides its constant changes of programme, the careful reading of the site would guarantee a far more extraordinary and original presence of the project. In the third stage the analysis of the immediate environment revealed localised rhythms of massing, distinct primary circulation flows, numerous secondary itineraries and clear orientational landmarks. In the broadest sense, the location of the Royal Palace and its resultant tourist pedestrian traffic drew a street (Xiyuan Avenue) through the site. The proximity of wider catchments of visitors, urban dwellers, university populations, business district employees and visitors with specific requirements of the site resulted in vehicular access and appropriate façades gravitating to the southern edges.

Throughout the intervention fluidity and variety of movement were embraced. The northern region employed small-scale massing of buildings, façades and routes that reflected the pace and scale of pedestrian movement. To the south, façade scales increased and routes broadened relative to the swifter, less personal vehicular traffic. In each case the presented public face was specifically appropriate. A variety of spatial densities and continuities of movement were employed to maximise the public experience of the site and to optimise the public/retail interface. The journey through the boundary of the intervention was transitional; from external environments, through access routes and ramps, via and between the primary buildings at ground level. A subtle barrier was provided to the externalised city. When the visitor arrived at the more introspective spaces of the site the pace slowed and the relationship with the architecture was concentrated. Retail and entertainment were encouraged in a sequence of buildings, protected courtyards, gardens, footpaths and streets organised perpendicularly to the North Boulevard and the South thoroughfare. Intimate, narrow streets and dramatic, spacious malls interconnected. A lattice of paths and sweeping roofs overlapped and occasionally merged in an exchange between buildings, hard landscape and green spaces.

Some aspects of traditional Chinese architecture continued to be interpreted, including the employment of specific buildings for particular functions (hotels and KTV), the implementation of a unit system similar to that of a traditional low-rise Chinese city (retail/entertainment units), the use of courtyards that would be accessed by a series of corridors (building interstices), and the intention of blending buildings with the natural surroundings (green belt and accessible roofs from the south side). Other aspects included a degree of transparency and sense of ambiguity between inside and outside spaces (as in the proposed Xiyuan Avenue), and the treatment of flat surfaces in a technological manner (CAD/CAM stone roof, metal and wooden screens), exploring abstraction and ornamental patters on their overall appearance.

Technological and cultural synthesis

In the last and final stage our increased familiarity with people, site, and background of Chinese architectural history convinced us that architecture in China today has to be experimental in order to become innovative. It must get rid of a long-standing dual thinking in which terms such as ‘essence and form’, ‘traditional and modern’, or ‘East and West’ were reducing the conceptual framework of a lot of the architectural discussion and production. In particular, the geographic differentiation and long-standing comparison between ‘East and West’ has become obsolete in a period in which the globalisation effect is allowing different lifestyles, because formal and technological know-how can be adopted rapidly and simultaneously in every part of the world. Hence our proposal was aiming at global sophistication within a local context. As much as observing the past, we concentrated on a meticulous integration of the project on such a vulnerable site, as well as interpreting the contemporary Chinese society—especially in terms of new habits and particular manners in which private and public spaces are appropriated. The proposed architecture had clearly to attend to the historical development of China’s socio-cultural space, as well as focus on the employment of groundbreaking technology that could combine high-tech manufacturing processes (China’s growing industrial know-how) and low-tech assemblage (China’s available labour). We envisioned a thoroughly contemporary and advanced structural and material building solution that would incorporate Chinese sensibility into a technological state-of-the-arts computerised design and construction process.

Three particular design and manufacturing technologies were to be adopted:

CAD/CAM milling technologies of different stones (perhaps traditional Jinshanshi, shanshi, black qinshi, and Nudoushi sandstone) were proposed for the vast roof surfaces and façades. As demonstrated in the recent achievements on Antoni Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia in Barcelona Spain, such CAD/CAM technology would provide an adequate and economic solution for similar design preoccupations. The result would resemble the sensibility of jade and red lacquer carvings, and of the marvellous marble carved stone in the Forbidden City. In fact, due to the proximity to such an important heritage site, we considered the roof landscape of the proposed buildings (constructed in different phases) a vast, contemplative, stone carpet that introduced the Summer Palace.

CAD/CAM laser, plasma, water-jet or oxy cutting techniques were to be used for the manufacturing of the main steel structure and some façades screens, as well as internal secondary structures and division walls. Because these technologies are long established in the shipbuilding industry and strongly expanding, such strategy would allow a precise and uncomplicated manufacturing of the structural skeleton of the buildings. On a smaller scale, we proposed a timber construction technique that we have been recurrently testing, whereby notched laser cut elements can be assembled without the need of nails or screws—similar to Chinese traditional timber temple structures.

CAD/CAM Rapid Prototyping techniques, which we are also researching with our students within the academic environment at the renowned Bartlett School of Architecture in London, would enable the manufacturing of specific pieces, as well as the production of precise scaled models. Thanks to the advancement of 3D engineering and hi-tech computerised design and manufacturing process, expensive skilled labour during assemblage is less required.

The motivation behind the design of the Xiyuan Entertainment Complex was mimesis rather than mimicry—association rather than imitation—of elements or aesthetics of great Chinese architecture. New available and affordable technologies must be used in order to place at the architect’s disposal new ways of expressing contemporariness and identity (of both the designer and the client).

Periods of American, Russian, and nowadays multinational influences have created crucial episodes in China’s architectural history. After straightforward copying of Western influences, followed by partial rejections, the incorporation of global phenomena is irreversible but should be now transcended. It is up to us architects today, regardless of nationality or provenience, to encroach in an international debate (maybe in the line of the ‘Great Cultural Discussion’) that is by default centred in China. The Orient-ation of architects world-wide towards the East is a sign of great hope for architecture today and the future.

Legend

The program of the Xiyuan Entertainment Complex is divided into two Major Entertainment Groups and eight Commercial Unit Buildings. The first group of Major Entertainment Groups include eight Cinemas, a KTV, Indoor Games, and an Exhibition Area. These facilities are located on the busier east side of the site close to the Underground station and the urban thoroughfare. They are grouped together into one building complex with a major distribution area (foyer) that simultaneously connects the upper ground floor entrances, proposed road and underground station on the –6 level. The exhibition area is located strategically between the North Boulevard and the main urban thoroughfare, whereas the KTV is placed on the most visible eastern corner of the side. The cluster of three hotel units is located on the calmer west side surrounded by a wall that safeguards and protects the peacefulness of the interiors.

A 500m long and 16 m wide road strip – the Xiyuan Avenue - through the middle of the site intersects each Unit Building, dividing it into a northern and a southern sector. The northern section is smaller and more appropriate to the pedestrian flow of tourists along the North Boulevard. The bigger southern sector contains larger inner units that relate more to the quicker pace of the high intensity car flow. From the Xiyuan Avenue, the grouping of all units into Unit Buildings enhances the intervention’s urban character, in particular through the variety of façades and in-between open spaces. From the south and north Boulevards, on the other hand, the gaps between buildings interweave gradually the landscape with the proposed built form, minimising the impact in such delicate site.

The sequence of these autonomously standing volumes organised the underneath common car park and also the use of the upper roof areas. It also allowed for a separate management of units, as well as a possible phasing during the construction time. The spaces between the Unit Buildings create a sequence of interstices through which outer and/or inner circulation between buildings and plazas on different levels is established. These interstices are designed to be circulation spaces that enable direct ventilation and insulation for the majority of units.

All individual Units inside the Unit Buildings are divided into duplex typologies with direct car access on the front façade (either from the South thoroughfare or the Xiyuan Avenue). In many cases there is also a pedestrian access provided on the floor underneath or above the duplex unit (either from the North Boulevard or the ground floor path along the Xiyuan Avenue, called Xiyuan Promenade).

Internal Circulation Nodes within the duplex units integrate staircases, escalators, toilets and/or small office spaces in an in-between mezzanine floor. Crossing staircases of two neighbouring units allow for a visual interchange between users of different units.

In order to achieve the percentage of green area required by the Beijing Municipality (30% of ground floor area), all buildings and roads where grouped into a dense cluster of buildings in the middle of the site, creating a green belt all around it. On the south side, the green area is larger than on the north side and is occupied with a barrier of dense and tall vegetation that shields the view towards the extensive wall along the South thoroughfare. This longitudinal urban park integrates external parking, pavements, recreation spots and several water pools. On the north Boulevard, the belt is kept narrow in order to allow a close contact between tourists that walk along the Boulevard and the facing building façades. The western part of the belt is proposed as a ramping surface for luxurious vegetation that surrounds the hotel volume touching the lower floors of the hotels. The ramping surface of the green area brings natural light and ventilation to the dining rooms and reception of each hotel in the –6 level.

There are three types of proposed plazas in the Xiyuan Entertainment Complex: two Sunken Plazas in the car park - The West Sunken Plaza and the East Sunken Plaza - a larger plaza on the –6 level – the Xiyuan Piazza - and several courtyards in the ground floor level of each building – the Upper Courtyards.

Design Team: marcosandmarjan with Jia Lu (Competition stage: with Jia Lu and Steve Pike)

Prof. Iain Borden

Head, Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

Xiyuan

It was high summer. The air was hot and humid, and the sizzling of the dragonflies revealed the close proximity to the adjacent Yiheyuan lake. We were looking eastwards, imagining the sun rising and shining tangentially over what we envisioned to be the vast stone surface of the Xiyuan Entertainment Complex. The atmosphere that day was going to be just magic…

The ‘Big Roof’ masquerade

Back in spring 2004 we had started working on an invited competition for the Xiyuan Complex, which we were later asked to develop further. The brief in that first stage was for a 180.000m2 building proposal on a long strip of land of around 100x750 metres located right in front of the gates to the Yiheyuan Royal Summer Palace in the Haidian district in northwest Beijing. Due to an imposed restriction of the building’s height to 3.3m, and consequently a lack of visibility, we were asked to cover the whole building with a series of traditional Chinese upturned tiled roofs that would give this intervention a conspicuous Chinese face. Here, the ‘Big Roof’ was a mask, a powerful symbol that would link a modern programme to the historical past of the Summer Palace. In the words of the Liang Sicheng the architecture would be ‘wearing a Western suit and a Chinese skullcap’.1 This ‘adaptive approach’ of a Western-style building hidden behind a Chinese-style roof was reminiscent of a long-lasting debate, in which a conceptual binary distinction between the notion of essence, body, foundation, content or structure (ti), as opposed to form, application, use and function (yong) had largely troubled Chinese architectural history.2

In the Xiyuan project, a sequence of distinctive interpenetrating roof structures, along with a series of courtyards—designed as protected yet public spaces—tried to extend the tremendously rich lineage of notable Chinese historical buildings, whilst translating such concepts through the requirements and intentions of a contemporary commercial intervention.

From mono-programmatic to multi-programmatic

Due to uncertainties regarding the financial viability of such programme—so common in contemporary China—the project went through considerable changes in a very short period of time. From an open and very permeable multi-purpose intervention with retail areas, conference facilities and public entertainment in the first stage, the project transfigured in the second stage into a mono-programmatic, large-scale shopping mall, and later into an entertainment complex. Fortunately, the idea of a highly marketed intervention under the brand name of a Western architect, characterised by the fake image of a ‘Big Roof’, was abolished. The roof controversy, however, remained, yet it was turned into a large accessible green area allowing a variety of recreational and sports facilities, which afterwards turned into a large stone surface.

Subtle contextualisation

Meanwhile, morphological and topographical nuances were increasingly shaping the proposal. This was furthered by our conviction that, besides its constant changes of programme, the careful reading of the site would guarantee a far more extraordinary and original presence of the project. In the third stage the analysis of the immediate environment revealed localised rhythms of massing, distinct primary circulation flows, numerous secondary itineraries and clear orientational landmarks. In the broadest sense, the location of the Royal Palace and its resultant tourist pedestrian traffic drew a street (Xiyuan Avenue) through the site. The proximity of wider catchments of visitors, urban dwellers, university populations, business district employees and visitors with specific requirements of the site resulted in vehicular access and appropriate façades gravitating to the southern edges.

Throughout the intervention fluidity and variety of movement were embraced. The northern region employed small-scale massing of buildings, façades and routes that reflected the pace and scale of pedestrian movement. To the south, façade scales increased and routes broadened relative to the swifter, less personal vehicular traffic. In each case the presented public face was specifically appropriate. A variety of spatial densities and continuities of movement were employed to maximise the public experience of the site and to optimise the public/retail interface. The journey through the boundary of the intervention was transitional; from external environments, through access routes and ramps, via and between the primary buildings at ground level. A subtle barrier was provided to the externalised city. When the visitor arrived at the more introspective spaces of the site the pace slowed and the relationship with the architecture was concentrated. Retail and entertainment were encouraged in a sequence of buildings, protected courtyards, gardens, footpaths and streets organised perpendicularly to the North Boulevard and the South thoroughfare. Intimate, narrow streets and dramatic, spacious malls interconnected. A lattice of paths and sweeping roofs overlapped and occasionally merged in an exchange between buildings, hard landscape and green spaces.

Some aspects of traditional Chinese architecture continued to be interpreted, including the employment of specific buildings for particular functions (hotels and KTV), the implementation of a unit system similar to that of a traditional low-rise Chinese city (retail/entertainment units), the use of courtyards that would be accessed by a series of corridors (building interstices), and the intention of blending buildings with the natural surroundings (green belt and accessible roofs from the south side). Other aspects included a degree of transparency and sense of ambiguity between inside and outside spaces (as in the proposed Xiyuan Avenue), and the treatment of flat surfaces in a technological manner (CAD/CAM stone roof, metal and wooden screens), exploring abstraction and ornamental patters on their overall appearance.

Technological and cultural synthesis

In the last and final stage our increased familiarity with people, site, and background of Chinese architectural history convinced us that architecture in China today has to be experimental in order to become innovative. It must get rid of a long-standing dual thinking in which terms such as ‘essence and form’, ‘traditional and modern’, or ‘East and West’ were reducing the conceptual framework of a lot of the architectural discussion and production. In particular, the geographic differentiation and long-standing comparison between ‘East and West’ has become obsolete in a period in which the globalisation effect is allowing different lifestyles, because formal and technological know-how can be adopted rapidly and simultaneously in every part of the world. Hence our proposal was aiming at global sophistication within a local context. As much as observing the past, we concentrated on a meticulous integration of the project on such a vulnerable site, as well as interpreting the contemporary Chinese society—especially in terms of new habits and particular manners in which private and public spaces are appropriated. The proposed architecture had clearly to attend to the historical development of China’s socio-cultural space, as well as focus on the employment of groundbreaking technology that could combine high-tech manufacturing processes (China’s growing industrial know-how) and low-tech assemblage (China’s available labour). We envisioned a thoroughly contemporary and advanced structural and material building solution that would incorporate Chinese sensibility into a technological state-of-the-arts computerised design and construction process.

Three particular design and manufacturing technologies were to be adopted:

CAD/CAM milling technologies of different stones (perhaps traditional Jinshanshi, shanshi, black qinshi, and Nudoushi sandstone) were proposed for the vast roof surfaces and façades. As demonstrated in the recent achievements on Antoni Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia in Barcelona Spain, such CAD/CAM technology would provide an adequate and economic solution for similar design preoccupations. The result would resemble the sensibility of jade and red lacquer carvings, and of the marvellous marble carved stone in the Forbidden City. In fact, due to the proximity to such an important heritage site, we considered the roof landscape of the proposed buildings (constructed in different phases) a vast, contemplative, stone carpet that introduced the Summer Palace.

CAD/CAM laser, plasma, water-jet or oxy cutting techniques were to be used for the manufacturing of the main steel structure and some façades screens, as well as internal secondary structures and division walls. Because these technologies are long established in the shipbuilding industry and strongly expanding, such strategy would allow a precise and uncomplicated manufacturing of the structural skeleton of the buildings. On a smaller scale, we proposed a timber construction technique that we have been recurrently testing, whereby notched laser cut elements can be assembled without the need of nails or screws—similar to Chinese traditional timber temple structures.

CAD/CAM Rapid Prototyping techniques, which we are also researching with our students within the academic environment at the renowned Bartlett School of Architecture in London, would enable the manufacturing of specific pieces, as well as the production of precise scaled models. Thanks to the advancement of 3D engineering and hi-tech computerised design and manufacturing process, expensive skilled labour during assemblage is less required.

The motivation behind the design of the Xiyuan Entertainment Complex was mimesis rather than mimicry—association rather than imitation—of elements or aesthetics of great Chinese architecture. New available and affordable technologies must be used in order to place at the architect’s disposal new ways of expressing contemporariness and identity (of both the designer and the client).

Periods of American, Russian, and nowadays multinational influences have created crucial episodes in China’s architectural history. After straightforward copying of Western influences, followed by partial rejections, the incorporation of global phenomena is irreversible but should be now transcended. It is up to us architects today, regardless of nationality or provenience, to encroach in an international debate (maybe in the line of the ‘Great Cultural Discussion’) that is by default centred in China. The Orient-ation of architects world-wide towards the East is a sign of great hope for architecture today and the future.

Legend

The program of the Xiyuan Entertainment Complex is divided into two Major Entertainment Groups and eight Commercial Unit Buildings. The first group of Major Entertainment Groups include eight Cinemas, a KTV, Indoor Games, and an Exhibition Area. These facilities are located on the busier east side of the site close to the Underground station and the urban thoroughfare. They are grouped together into one building complex with a major distribution area (foyer) that simultaneously connects the upper ground floor entrances, proposed road and underground station on the –6 level. The exhibition area is located strategically between the North Boulevard and the main urban thoroughfare, whereas the KTV is placed on the most visible eastern corner of the side. The cluster of three hotel units is located on the calmer west side surrounded by a wall that safeguards and protects the peacefulness of the interiors.

A 500m long and 16 m wide road strip – the Xiyuan Avenue - through the middle of the site intersects each Unit Building, dividing it into a northern and a southern sector. The northern section is smaller and more appropriate to the pedestrian flow of tourists along the North Boulevard. The bigger southern sector contains larger inner units that relate more to the quicker pace of the high intensity car flow. From the Xiyuan Avenue, the grouping of all units into Unit Buildings enhances the intervention’s urban character, in particular through the variety of façades and in-between open spaces. From the south and north Boulevards, on the other hand, the gaps between buildings interweave gradually the landscape with the proposed built form, minimising the impact in such delicate site.

The sequence of these autonomously standing volumes organised the underneath common car park and also the use of the upper roof areas. It also allowed for a separate management of units, as well as a possible phasing during the construction time. The spaces between the Unit Buildings create a sequence of interstices through which outer and/or inner circulation between buildings and plazas on different levels is established. These interstices are designed to be circulation spaces that enable direct ventilation and insulation for the majority of units.

All individual Units inside the Unit Buildings are divided into duplex typologies with direct car access on the front façade (either from the South thoroughfare or the Xiyuan Avenue). In many cases there is also a pedestrian access provided on the floor underneath or above the duplex unit (either from the North Boulevard or the ground floor path along the Xiyuan Avenue, called Xiyuan Promenade).

Internal Circulation Nodes within the duplex units integrate staircases, escalators, toilets and/or small office spaces in an in-between mezzanine floor. Crossing staircases of two neighbouring units allow for a visual interchange between users of different units.

In order to achieve the percentage of green area required by the Beijing Municipality (30% of ground floor area), all buildings and roads where grouped into a dense cluster of buildings in the middle of the site, creating a green belt all around it. On the south side, the green area is larger than on the north side and is occupied with a barrier of dense and tall vegetation that shields the view towards the extensive wall along the South thoroughfare. This longitudinal urban park integrates external parking, pavements, recreation spots and several water pools. On the north Boulevard, the belt is kept narrow in order to allow a close contact between tourists that walk along the Boulevard and the facing building façades. The western part of the belt is proposed as a ramping surface for luxurious vegetation that surrounds the hotel volume touching the lower floors of the hotels. The ramping surface of the green area brings natural light and ventilation to the dining rooms and reception of each hotel in the –6 level.

There are three types of proposed plazas in the Xiyuan Entertainment Complex: two Sunken Plazas in the car park - The West Sunken Plaza and the East Sunken Plaza - a larger plaza on the –6 level – the Xiyuan Piazza - and several courtyards in the ground floor level of each building – the Upper Courtyards.

Design Team: marcosandmarjan with Jia Lu (Competition stage: with Jia Lu and Steve Pike)

Collaborators: Nat Keast, Shaun Siu Chong, James Pike, Sirichai Bunchua, Mark Exon, Samuel White, Keith Watson, Andy Shawn, Kenny Tsui, Tamsin Green, Jessica Lee

Total Built Area 180.000 m2

Ground floor area 56.000 m2

Basement area on –6 level 56.000 m2

Basement on –9.6 level 50.000 m2 (car park) + 6.000 m2 (units)

Road and external circulation 12.000 m2

Notes:

1 Referred by Peter Rowe and Zeng Kuan in Architectural Encounters with Essence and Form in Modern China, The MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, 2002 (p. 95)

2 According to Peter Rowe and Zeng Kuan this differentiation emerged during the ‘Self-Strengthening Movement’ of the late nineteenth century in China and remained central in later moments, such as the Hundred Day’s Reform and Constitutional Movement, the May Fourth movement, the Republican and Nationalist period, as well as in Mao’s reformulation period (although in this period discussed with another terminology).

zebo_Bartlett+1.jpg)